Recently, one of our clients needed a Windows DLL implemented that exported C++ objects compatible with their existing application when run under Wine. While this was new to me, this is actually something we already do in Wine. We have implementations of Microsoft's Visual Studio C++ runtime objects, which are used by lots of applications. Applications which use those objects expect to get C++ objects from Windows DLLs like msvcp.

I've never worked with this code before, and I don't do a lot of assembly-level work, so it was a fun learning experience for me. Wine is a C-language project, but we export C++ objects that are compatible with applications built on Windows. We even support Visual Studio RTTI data, constructors, destructors, and so on. I actually got lucky: my project pretty much just needed C++ class function calls, no constructors or RTTI data, so I was able to skip a lot of the complication. The method we use to export Windows-style C++ objects from a C library built on a Unix system is pretty interesting. Here's how it works.

Let's start at the end. Here's the relevant code from Wine's <dlls/msvcrt/cxx.h>, slightly simplified:

#define THISCALL(func) __thiscall_ ## func

#define DEFINE_THISCALL_WRAPPER(func) \

extern void THISCALL(func)(void); \

__ASM_GLOBAL_FUNC(__thiscall_ ## func, \

"popl %eax\n\t" \

"pushl %ecx\n\t" \

"pushl %eax\n\t" \

"jmp " #func )

A little git-fu shows it dates from 2003 and was written by Alexandre Julliard, the Wine project's leader and

maintainer, with some improvements made later. Here's a trivial sample of how

it's used:

typedef struct _MyCPPObject {

vtable_ptr *vtable;

int internal_data;

} MyCPPObject;

DEFINE_THISCALL_WRAPPER(MyCPPObject_doSomething)

int __stdcall MyCPPObject_doSomething(MyCPPObject *_this, int a, int b)

{

this->internal_data += a;

return this->internal_data + b;

}

What's going on here? Let's talk about calling conventions.When your code makes a call into a function, there must be some way to pass your call's arguments into that function. This is done through some combination of storing data on the stack and in the registers. There is no clearly best way to do this, so of course a few dozen different ways have been created over the past few decades, all of which are equally good. These are the calling conventions.

We're concerned here with just two conventions for the x86 architecture:

thiscall, and the hilariously

optimistically named stdcall. thiscall itself actually has two sub-conventions,

one when built by GCC (and Clang?) and another when built by Visual Studio.

First let's discuss

stdcall. This is the default convention used by Visual

Studio when building plain C functions. stdcall stores its arguments entirely

on the stack, in right-to-left order, followed by the instruction pointer to

which the function should return:

The called function is allowed to clobber the data in registers

EAX, ECX, and EDX, but

must save and restore the data in all other registers so they contain the same

data when the function exits. When the function returns, EAX stores the return

value for use by the caller.

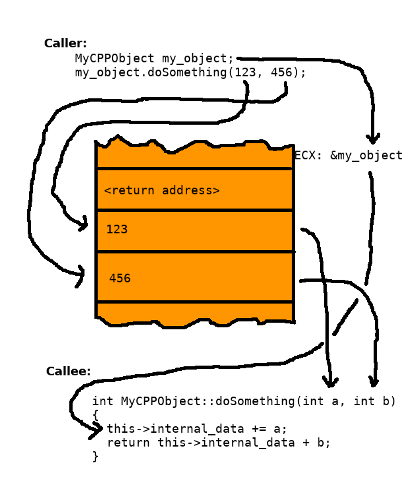

That makes sense. But what happens with a C++ call?

MyCPPObject my_object; int r = my_object.doSomething(123, 456);One way a C++ compiler could handle this is to treat the

my_object pointer as a

hidden parameter and pass it in to the MyCPPObject::doSomething function and

then apply the normal calling convention for your platform:

MyCPPObject::doSomething(my_object, 123, 456);This is the GCC variant of

thiscall. Since we're only dealing with application

code built by Visual Studio, we don't care about the GCC variant here, but it

will sound familiar in a moment.

Visual Studio does something different. The Visual Studio version of

thiscall

is the same as stdcall, discussed above, but stores the this-pointer in ECX

instead of on the stack:

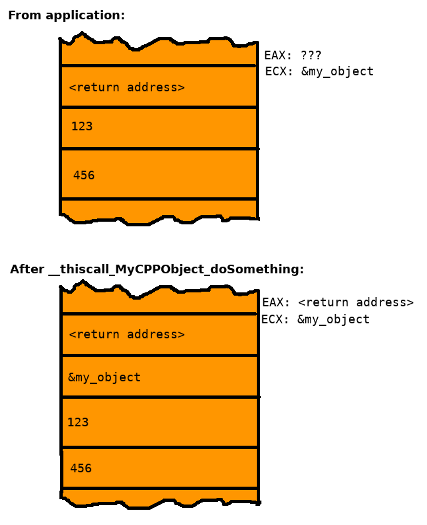

You can start to see where this is going. Let's take another look at the Wine-style, C language implementation of

MyCPPObject::doSomething from earlier, after running it

through the C preprocessor:

extern void __thiscall_MyCPPObject_doSomething(void);

__ASM_GLOBAL_FUNC(__thiscall_MyCPPObject_doSomething,

"popl %eax\n\t"

"pushl %ecx\n\t"

"pushl %eax\n\t"

"jmp MyCPPObject_doSomething")

int __stdcall MyCPPObject_doSomething(MyCPPObject *_this, int a, int b)

{

this->internal_data += a;

return this->internal_data + b;

}

Don't worry about __ASM_GLOBAL_FUNC, it just contains the assembly language

boilerplate to declare a new function. I also haven't gotten into how the

vtable works or how the object is allocated, but know that

__thiscall_MyCPPObject_doSomething is our entry point from the Windows

application's code.

You can see from that snippet that

__thiscall_MyCPPObject_doSomething first pops off the top of the stack, which

contains the return address, into EAX, which we can clobber. Then it pushes the

value of ECX and then EAX back onto the stack, then jumps to our real

doSomething implementation, which is just below. Here's what happens to the stack before and after that transformation:

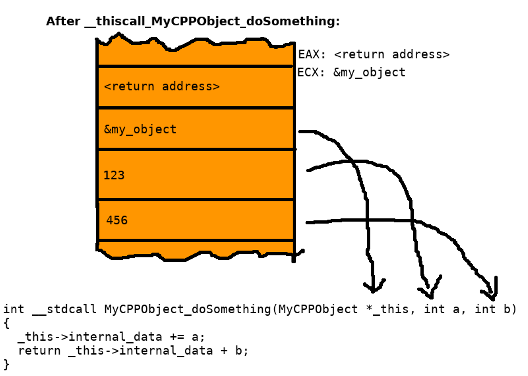

And now we've got a

stdcall-compatible stack containing our

this-pointer:

That's what it takes to convert a Visual Studio

thiscall C++ call into a

stdcall convention call that we can work with in a C language file, with no changes to the

original C++ application.Interested in learning more tips and tricks about Wine programming? Tell us about it in the comments section.

Curious about our contribution to the Wine project? Click here to learn more about it.

About Andrew Eikum

Andrew was a former Wine developer at CodeWeavers from 2009 to 2022. He worked on all parts of Wine, but specifically supported Wine's audio. He was also a developer on many of CodeWeavers's PortJumps.

Andrew Eikum

Andrew Eikum